Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Comparison of Features and Implementation in Grin vs. BEAM

- Proof of Work Mining Algorithm

- Governance Models and Monetary Policy

- Conclusions, Observations and Recommendations

- References

- Appendices

- Contributors

Introduction

Grin and BEAM are two open-source cryptocurrency projects based on the Mimblewimble protocol. The Mimblewimble protocol was first proposed by an anonymous user using the pseudonym Tom Elvis Jedusor (the French translation of Voldemort’s name from the Harry Potter series of books). This user logged onto a bitcoin research Internet Relay Chat (IRC) channel and posted a link to a text article hosted on a Tor hidden service [1]. This article provided the basis for a new way to construct blockchain-style transactions that provided inherent privacy and the ability to dramatically reduce the size of the blockchain by compressing the transaction history of the chain. The initial article presented the main ideas of the protocol, but left out a number of critical elements required for a practical implementation and even contained a mistake in the cryptographic formulation. Andrew Poelstra published a follow-up paper that addresses many of these issues and refines the core concepts of Mimblewimble [2], which have been applied to the practical implementation of this protocol in both the Grin [[3]] and BEAM [[4]] projects.

The Mimblewimble protocol describes how transacting parties will interactively work to build a valid transaction using their public/private key pairs (which are used to prove ownership of transaction outputs) and interactively chosen blinding factors. Blinding factors are used to obfuscate the participants’ public keys from everyone, including each other, and to hide the value of the transaction from everyone except the counterparty in that specific transaction. The protocol also performs a process called cut-through, which condenses transactions by eliminating intermediary transactions. This improves privacy and compresses the amount of data that is maintained on the blockchain [[3]]. This cut-through process precludes general-purpose scripting systems such as those found in Bitcoin. However, Andrew Poelstra proposed the concept of Scriptless scripts, which make use of Schnorr signatures to build adaptor signatures that allow for encoding of many of the behaviors that scripts are traditionally used to achieve. Scriptless scripts enable functionality such as payment channels (e.g. Lightning Network) and atomic swaps [[5]].

The Grin and BEAM projects both implement the Mimblewimble protocol, but both have been built from scratch. Grin is written in RUST and BEAM in C++. This report describes some of the aspects of each project that set them apart. Both projects are still in their early development cycles and many of these details are changing on a daily basis. Furthermore, the BEAM project documentation is mostly available only in Russian. As of the writing of this report, not all the technical details are available for English readers. Therefore the discussion in this report will most likely become outdated as the projects evolve.

This report is structured as follows:

- Firstly, some implementation details are given and unique features of the projects are discussed.

- Secondly, the differences in the projects’ Proof-of-Work (PoW) algorithms are examined.

- Finally, the projects’ governance models are discussed.

Comparison of Features and Implementation in Grin vs. BEAM

The two projects are being independently built from scratch by different teams in different languages (Rust [6] and C++ [7]), so there will be many differences in the raw implementations. For example, Grin uses the Lightning Memory-mapped Database (LMDB) for its embedded database and BEAM uses SQLite. Although they have performance differences, they are functionally similar. Grin uses a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) to represent its mempool to avoid transaction reference loops [8], while BEAM uses a multiset key-value data structure with logic to enable some of its extended features [7].

From the perspective of features, the two projects exhibit all the features inherent to Mimblewimble. Grin’s stated goal is to produce a simple and easy to maintain implementation of the Mimblewimble protocol [[3]]. BEAM’s implementation, however, contains a number of modifications to the Mimblewimble approach, with the aim to provide some unique features for its implementation. Before we get into the features and design elements that set the two projects apart, let’s discuss an interesting feature that both projects have implemented.

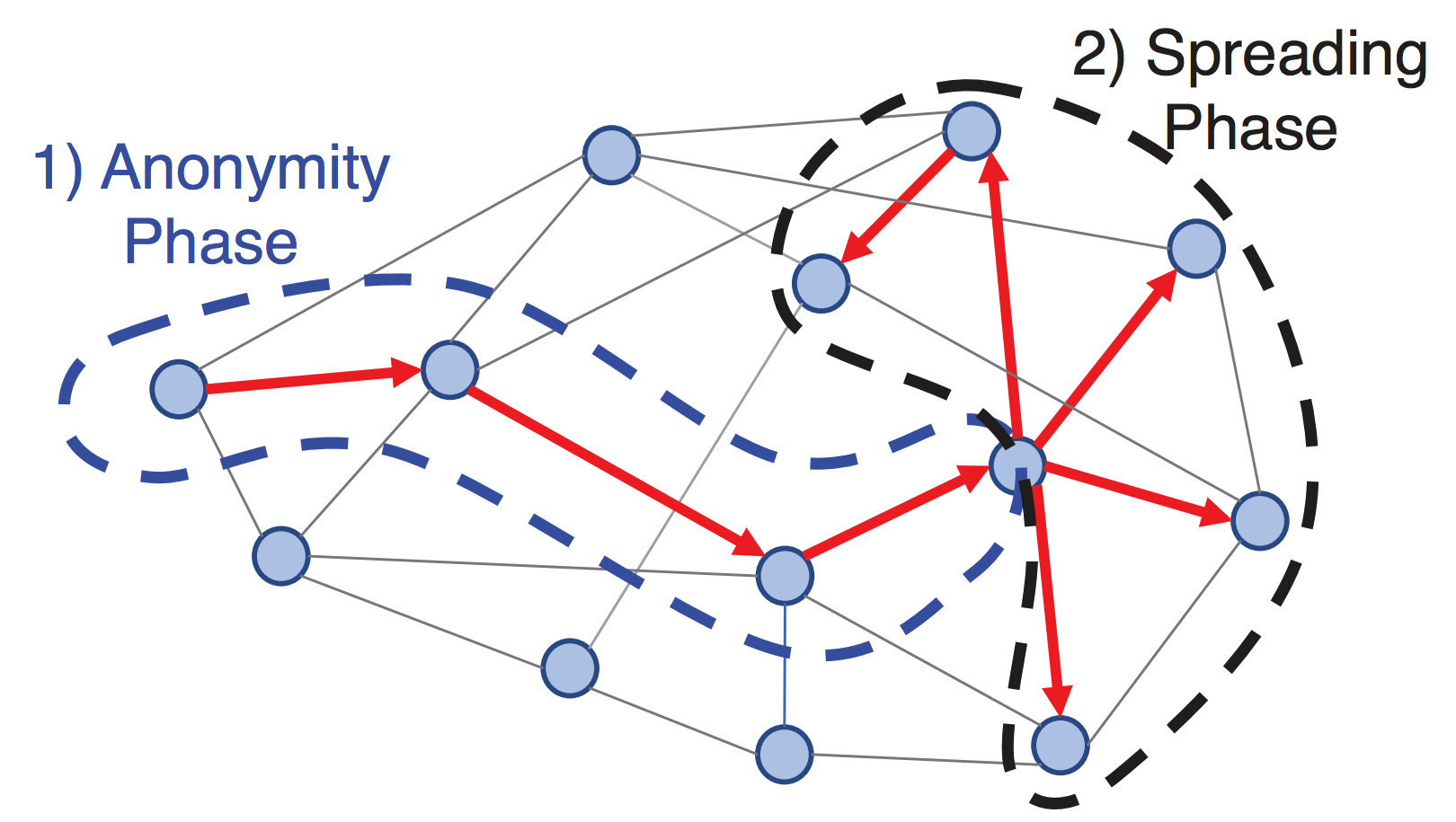

Both Grin and BEAM have incorporated a version of the Dandelion relay protocol, which supports transaction aggregation. One of the major outstanding challenges for privacy that cryptocurrencies face is that it is possible to track transactions as they are added to the mempool and propagate across the network, and to link those transactions to their originating IP addresses. This information can be used to deanonymize users, even on networks with strong transaction privacy. The Dandelion network propagation scheme was proposed to improve privacy during the propagation of transactions to the network [[9]]. In this scheme, transactions are propagated in two phases: the Anonymity (or “stem”) phase and the Spreading (or “fluff”) phase, as illustrated in Figure 1.

-

In the stem (anonymity) phase, a transaction is propagated to only a single randomly selected peer from the current node’s peer list. After a random number of hops along the network, each hop propagating to only a single random peer, the propagation process enters the second phase.

-

During the fluff (spreading) phase, the transaction is propagated using a full flood/diffusion method, as found in most networks. This approach means that the transaction has first propagated to a random point in the network before flooding the network, thereby making it much more difficult to track its origin.

Both projects have adapted this approach to work with Mimblewimble transactions. Grin’s implementation allows for transaction aggregation and cut-through in the stem phase of propagation, which provides even greater anonymity to the transactions before they spread during the fluff phase [[10]]. In addition to transaction aggregation and cut-through, BEAM introduces “dummy” transactions that are added in the stem phase to compensate for situations when real transactions are not available [[33]].

Grin Unique Features

Grin is aiming to be a simple and minimal reference implementation of a Mimblewimble blockchain. It is therefore not aiming to include many features to extend the core Mimblewimble functionality, as discussed. However, the Grin implementation does include some interesting implementation choices that it has documented in depth on its growing Github repository’s wiki.

For example, Grin has implemented a method for a node to sync the blockchain very quickly by only downloading a partial history [11]. A new node entering the network will query the current head block of the chain and then request the block header at a horizon. In the example, the horizon is initially set at 5,000 blocks before the current head. The node then checks if there is enough data to confirm consensus. If there isn’t consensus, the node will increase its horizon until consensus is reached. At that point, it will download the full Unspent Transaction Output (UTXO) set of the horizon block. This approach does introduce a few security risks, but mitigations are provided and the result is that a node can sync to the network with an order of magnitude less data.

Since the initial writing of this article (October 2018), BEAM has published its solution for fast node synchronization using macroblocks. A macroblock is a complete state of all UTXOs, periodically created by BEAM nodes [[12]].

BEAM Unique Features

BEAM has set out to extend the feature set of Mimblewimble in a number of ways. BEAM supports setting an explicit incubation period on a UTXO, which limits its ability to be spent to a specific number of blocks after its creation [[13]]. This is different to a timelock, which prevents a transaction from being added to a block before a certain time. BEAM also supports the traditional timelock feature, but includes the ability to also specify an upper time limit, after which the transaction can no longer be included in a block [[13]]. This feature means that a party can be sure that if a transaction is not included in a block on the main blockchain after a certain time, it will never appear.

Another unique feature of BEAM is the implementation of an auditable wallet. For a business to operate in a given regulatory environment, it will need to demonstrate its compliance to the relevant authorities. BEAM has proposed a wallet designed for compliant businesses, which generates additional public/private key pairs specifically for audit purposes. These signatures are used to tag transactions so that only the auditing authority that is given the public key can identify those transactions on the blockchain, but cannot create transactions with this tag. This allows a business to provide visibility of its transactions to a given authority without compromising its privacy to the public [14].

BEAM’s implementation of Dandelion improves privacy by adding decoy transaction outputs at the stem phase. Each such output has a value of zero, but is indistinguishable from regular outputs. At a later stage (a randomly calculated number of blocks for each output), the UTXOs are added as inputs to new transactions, thus spending them and removing them from the blockchain.

BEAM has also proposed another feature aimed at keeping the blockchain as compact as possible. In Mimblewimble, as transactions are added, cut-through is performed, which eliminates all intermediary transaction commitments [[3]]. However, the transaction kernels for every transaction are never removed. BEAM has proposed a scheme to reuse these transaction kernels to validate subsequent transactions [[13]]. In order to consume the existing kernels without compromising the transaction irreversibility principle, BEAM proposes that a multiplier be applied to an old kernel by the same user who has visibility of the old kernel, and that this be used in a new transaction. In order to incentivize transactions to be built in this way, BEAM includes a fee refund model for these types of transactions. This feature will not be part of the initial release.

When constructing a valid Mimblewimble transaction, the parties involved need to collaborate in order to choose blinding factors that balance. This interactive negotiation requires a number of steps and it implies that the parties need to be in communication to finalize the transaction. Grin facilitates this process by the two parties connecting directly to one another using a socket-based channel for a “real-time” session. This means that both parties need to be online simultaneously. BEAM has implemented a Secure Bulletin Board System (SBBS) that is run on BEAM full-nodes to allow for asynchronous negotiation of transactions ([[30]], [31]).

Requiring the interactive participation of both parties in constructing a transaction can be a point of friction in using a Mimblewimble blockchain. In addition to the secure BBS communication channel, BEAM also plans to support one-sided transactions where the payee in a transaction who expects to be paid a certain amount can construct their half of the transaction and send this half-constructed transaction to the payer. The payer can then finish constructing the transaction and publish it to the blockchain. Under the normal Mimblewimble system this is not possible, because it would involve revealing your blinding factor to the counterparty. BEAM solves this problem by using a process it calls kernel fusion, whereby a kernel can include a reference to another kernel so that it is only valid if both kernels are present in the transaction. In this way, the payee can build their half of the transaction with a secret blinding factor and a kernel that compensates for their blinding factor, which must be included when the payer completes the transaction [[13]].

Both projects make use of a number of Merkle tree structures to keep track of various aspects of the respective blockchains. Details of the exact trees and what they record are documented for both projects ([16], [17]). BEAM, however, makes use of a Radix-Hash tree structure for some of its trees. This structure is a modified Merkle tree that is also a binary search tree. This provides a number of features that the standard Merkle trees do not have, and which BEAM exploits in its implementation [17].

The features discussed here can all be seen in the code at the time of writing (May 2019), although this is not a guarantee that they are working. A couple of features, which have been mentioned in the literature as planned for the future, have not yet been implemented. These include embedding signed textual content into transactions that can be used to record contract text [[13]], and issuing confidential assets [18].

Proof-of-Work Mining Algorithm

BEAM has announced that it will employ the Equihash PoW mining algorithm with the parameters set to n=150, k=5 [32]. Equihash was proposed in 2016 as a memory-hard PoW algorithm that relied heavily on memory usage to achieve Application Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC) resistance [[19]]. The goal was to produce an algorithm that would be more efficient to run on consumer Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) as opposed to the growing field of ASIC miners, mainly produced by Bitmain at the time. It was hoped this would assist cryptocurrencies that used this algorithm, to decentralize the mining power. The idea behind Equihash’s ASIC resistance was that at the time, implementing memory in an ASIC was expensive and GPUs were more efficient at calculating the Equihash PoW. This ASIC resistance lasted for a while, but in early 2018, Bitmain released an ASIC for Equihash that was significantly more efficient than GPUs for the Equihash configurations used by Zcash, Bitcoin Gold and Zencash, to name a few. It is possible to tweak the parameters of the Equihash algorithm to make it more memory intensive and thus make current ASICs and the older GPU mining farms obsolete, but it remains to be seen if BEAM will do this. No block time has been published at the time of writing of this report (May 2019).

Grin initially opted to use the new Cuckoo Cycle PoW algorithm, also purported to be ASIC resistant due to being memory latency bound [20]. This means that the algorithm is bound by memory bandwidth rather than raw processor speed, with the hope that it will make mining possible on commodity hardware.

In August 2018, the Grin team announced at the launch of its mainnet that it had become aware that it was likely that an ASIC would be available for the Cuckoo cycle algorithm [21]. While acknowledging that ASIC mining is inevitable, Grin is concerned that the current ASIC market is very centralized (i.e. Bitmain), and it wants to foster a grassroots GPU mining community for two years, in the early days of Grin. After two years, Grin hopes that ASICs will have become more of a commodity and thus decentralized.

To address this, it was proposed to use two PoW algorithms initially: one that is ASIC Friendly (AF) and one that is ASIC Resistant (AR), and then to select which PoW is used per block to balance the mining rewards between the two algorithms, over a 24‑hour period. The Governance committee resolved on 25 September 2018 to go ahead with this approach, using a modified version of the Cuckoo Cycle algorithm, called the Cuckatoo Cycle. The AF algorithm at launch will be Cuckatoo32+, which will gradually increase its memory requirements to make older single-chip ASICs obsolete over time. The AR algorithm is still not defined [[23]].

Governance Models and Monetary Policy

Both the Grin and BEAM projects are open-source and available on Github ([6], [7]). The Grin project has 75 contributors, eight of which have contributed the vast majority of the code. BEAM has 10 contributors, four of which have contributed the vast majority of the code (at the time of writing). The two projects have opted for different models of governance. BEAM has opted to set up a foundation that includes the core developers, to manage the project. This is the route taken by most cryptocurrency projects in this space. The Grin community has decided against setting up a central foundation and has compiled an interesting discussion of the pros and cons of a centralized foundation [22]. This document contains a very in-depth discussion that weighs up the various governance functions that a foundation might serve, and evaluates each use case. The Grin community came to the conclusion that while foundations are useful, they do not provide the only solution to governance problems, and have therefore opted to remain a completely decentralized community-driven project. Currently, decisions are made at periodic governance meetings that are convened on Gitter with community members, where an agenda is discussed and decisions are ratified. Agendas and minutes of these meetings can be found in the Grin Forums governance section. An example of the outcomes of such a meeting can be seen in [[23]].

Neither project will engage in an Initial Coin Offering (ICO) or pre-mine, but the two projects also have different funding models. BEAM set up a Limited Liability Company (LLC) and has attracted investors to it for its initial round of non-profit BEAM Foundation that will take over the management of the protocol during the first year after launch [24]. The goal of the Foundation will be to support maintenance and further development of BEAM; promote relevant cryptographic research; support awareness and education in the areas of financial privacy; and support academic work in adjacent areas. In the industry, this treasury mechanism is called a dev tax. Grin will not levy a dev tax on the mining rewards, and will rely on community participation and community funding. The Grin project does accept financial support, but these funding campaigns are conducted according to their “Community Funding Principles” [25], which will be conducted on a “need-by-need” basis. A campaign will specify a specific need it aims to fulfill (e.g. “Hosting fees for X for the next year”) and the funding will be received by the community member who ran the campaign. This will provide 100% visibility regarding who is responsible for the received funds. An example of a funding campaign is the Developer Funding Campaign run by Yeastplume to fund his full-time involvement in the project from October 2018 to February 2019.

In terms of the monetary policy of the two projects, BEAM has stated that it will be using a deflationary model with periodic halving of its mining reward and a maximum supply of BEAM of 262,800,000 coins. BEAM will start with 100 coins emitted per block. The first halving will occur after one year. Halving will then happen every four years [32]. Grin has opted for an inflationary model where the block reward will remain constant, making its arguments for this approach in [27]. This approach will asymptotically tend towards a zero percent dilution as the supply increases, instead of enforcing a set supply [[28]]. Grin has not yet specified its mining reward or fees structure, but based on its current documentation, it is planning on a 60 grin per block reward. Neither project has made a final decision regarding how to structure fees, but the Grin project has started to explore how to set a fee baseline by using a metric of “fees per reward per minute” [[28]].

Conclusions, Observations and Recommendations

In summary, Grin and BEAM are two open-source projects that are implementing the Mimblewimble blockchain scheme. Both projects are building from scratch. Grin uses Rust while BEAM uses C++; therefore there are many technical differences in their design and implementation. However, from a functional perspective, both projects will support all the core Mimblewimble functionality. Each project does contain some unique functionality, but as Grin’s goal is to produce a minimalistic implementation of Mimblewimble, most of the unique features that extend Mimblewimble lie in the BEAM project. The following list summarizes the functional similarities and differences between the two projects.

- Similarities:

- Core Mimblewimble feature set.

- Dandelion relay protocol.

- Grin unique features:

- Partial history syncing.

- DAG representation of Mempool to prevent duplicate UTXOs and cyclic transaction references.

- BEAM unique features:

- Secure BBS hosted on the nodes for establishing communication between wallets. Removes the need for sender and receiver to be online at the same time.

- Use of decoy outputs in Dandelion stem phase. Decoy outputs are later spent to avoid clutter on blockchain.

- Explicit UTXO incubation period.

- Timelocks with a minimum and maximum threshold.

- Auditable transactions as part of the roadmap.

- One-sided transaction construction for non-interactive payments.

- Use of Radix-Hash trees.

Both projects are still very young. At the time of writing this report (May 2019), both are still in the testnet phase, and many of their core design choices have not yet been built or tested. Much of the BEAM wiki is still in Russian, so it is likely that there are details to which we are not yet privy. It will be interesting to keep an eye on these projects to see how their various decisions play out, both technically and in terms of their monetary policy and governance models.

References

[1] T. E. Jedusor, “MIMBLEWIMBLE” [online]. Available: https://download.wpsoftware.net/bitcoin/wizardry/mimblewimble.txt. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[2] A. Poelstra, “Mimblewimble” [online]. Available: https://download.wpsoftware.net/bitcoin/wizardry/mimblewimble.pdf. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[[3]] “Introduction to Mimblewimble and Grin” [online]. Available: https://github.com/mimblewimble/grin/blob/master/doc/intro.md. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[3]: https://github.com/mimblewimble/grin/blob/master/doc/intro.md ‘Introduction to Mimblewimble and Grin’

[[4]] “BEAM: The Scalable Confidential Cryptocurrency” [online]. Available: https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/87affd_3b032677d12b43ceb53fa38d5948cb08.pdf. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑28.

[4]: https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/87affd_3b032677d12b43ceb53fa38d5948cb08.pdf ‘BEAM: The Scalable Confidential Cryptocurrency’

[[5]] A. Gibson, “Flipping the Scriptless Script on Schnorr” [online]. Available: https://joinmarket.me/blog/blog/flipping-the-scriptless-script-on-schnorr/. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[5]: https://joinmarket.me/blog/blog/flipping-the-scriptless-script-on-schnorr/ ‘Flipping the Scriptless Script on Schnorr’

[6] “Grin Github Repository” [online]. Available: https://github.com/mimblewimble/grin. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[7] “BEAM Github Repository” [online]. Available: https://github.com/beam-mw/beam. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[8] “Grin - Transaction Pool” [online]. Available: https://github.com/mimblewimble/grin/blob/master/doc/internal/pool.md. Date accessed: 2018‑10‑22.

[[9]] S. B. Venkatakrishnan, G. Fanti and P. Viswanath, “Dandelion: Redesigning the Bitcoin Network for Anonymity” [online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1701.04439. Proc. ACM Meas. Anal. Comput. Syst. 1, 1, 2017. Date accessed: 2018‑10‑22.

[9]: https://arxiv.org/abs/1701.04439 ‘Dandelion: Redesigning the Bitcoin Network for Anonymity’

[[10]] “Dandelion in Grin: Privacy-Preserving Transaction Aggregation and Propagation” [online]. Available: https://github.com/mimblewimble/grin/blob/master/doc/dandelion/dandelion.md. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[10]: https://github.com/mimblewimble/grin/blob/master/doc/dandelion/dandelion.md ‘Dandelion in Grin: Privacy-Preserving Transaction Aggregation and Propagation’

[11] “Grin - Blockchain Syncing” [online]. Available: https://github.com/mimblewimble/grin/blob/master/doc/chain/chain_sync.md. Date accessed: 2018‑10‑22.

[[12]] “BEAM - Node Initialization Synchronization” [online]. Available: https://github.com/beam-mw/beam/wiki/Node-initial-synchronization. Date accessed: 2018‑12‑24.

[12]: https://github.com/beam-mw/beam/wiki/Node-initial-synchronization ‘BEAM - Node Initialization Synchronization’

[[13]] “BEAM Description. Comparison with Classical MW” [online]. Available: https://www.scribd.com/document/385080303/BEAM-Description-Comparison-With-Classical-MW. Date accessed: 2018‑10‑18.

[13]: https://www.scribd.com/document/385080303/BEAM-Description-Comparison-With-Classical-MW ‘BEAM Description. Comparison with Classical MW’

[14] “BEAM - Wallet Audit” [online]. Available: https://github.com/beam-mw/beam/wiki/Wallet-audit. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[[15]] “Beam’s Offline Transaction using Secure BBS System” [online]. Available: https://www.reddit.com/r/beamprivacy/comments/9fqbfg/beams_offline_transactions_using_secure_bbs_system. Date accessed: 2018‑10‑22.

[15]: https://www.reddit.com/r/beamprivacy/comments/9fqbfg/beams_offline_transactions_using_secure_bbs_system/ “Beam’s Offline Transaction using Secure BBS System”

[16] “GRIN - Merkle Structures” [online]. Available: https://github.com/mimblewimble/grin/blob/master/doc/merkle.md. Date accessed: 2018‑10‑22.

[17] “BEAM - Merkle Trees” [online]. Available: https://github.com/beam-mw/beam/wiki/Merkle-trees. Date accessed: 2018‑10‑22.

[18] “BEAM - Confidential Assets” [online]. Available: https://github.com/beam-mw/beam/wiki/Confidential-assets. Date accessed: 2018‑10‑22.

[[19]] A. Biryukov and D. Khovratovich, “Equihash: Asymmetric Proof-of-work based on the Generalized Birthday Problem” [online] Available: https://www.cryptolux.org/images/b/b9/Equihash.pdf. Proceedings of NDSS, 2016. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[19]: https://www.cryptolux.org/images/b/b9/Equihash.pdf ‘Equihash: Asymmetric Proof-of-work based on the Generalized Birthday Problem’

[20] “Cuckoo Cycle” [online]. Available: https://github.com/tromp/cuckoo. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[21] I. Peverell, “Proof of Work Update” [online]. Available: https://www.grin-forum.org/t/proof-of-work-update/713. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[22] “Regarding Foundations” [online]. Available: https://github.com/mimblewimble/docs/wiki/Regarding-Foundations. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[[23]] “Meeting Notes: Governance, Sep 25 2018” [online]. Available: https://www.grin-forum.org/t/meeting-notes-governance-sep-25-2018/874. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[23]: https://www.grin-forum.org/t/meeting-notes-governance-sep-25-2018/874 ‘Meeting Notes: Governance, Sep 25 2018’

[24] “BEAM Features” [online]. Available: https://www.beam.mw. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[25] “Grin’s Community Funding Principles” [online]. Available: https://grin-tech.org/funding.html. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑28.

[27] “Monetary Policy” [online]. Available: https://github.com/mimblewimble/docs/wiki/Monetary-Policy. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[[28]] “Economic Policy: Fees and Mining Reward” [online]. Available: https://github.com/mimblewimble/grin/wiki/fees-mining. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[28]: https://github.com/mimblewimble/grin/wiki/fees-mining ‘Economic Policy: Fees and Mining Reward’

[29] “Grin’s Proof-of-Work” [online]. Available: https://github.com/mimblewimble/grin/blob/master/doc/pow/pow.md. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑30.

[[30]]: R Lahat, “The Secure Bulletin Board System (SBBS) Implementation in Beam” [online]. Available: https://medium.com/beam-mw/the-secure-bulletin-board-system-sbbs-implementation-in-beam-a01b91c0e919. Date accessed: 2018‑12‑24.

[30]: https://medium.com/beam-mw/the-secure-bulletin-board-system-sbbs-implementation-in-beam-a01b91c0e919 ‘The Secure Bulletin Board System (SBBS) Implementation in Beam’

[31]: “Secure Bulletin Board System (SBBS)” [online]. Available: https://github.com/BeamMW/beam/wiki/Secure-bulletin-board-system-(SBBS). Date accessed: 2018‑12‑24.

[32]: “Beam’s Mining Specification” [online]. Available: https://github.com/BeamMW/beam/wiki/BEAM-Mining. Date accessed: 2018‑12‑24.

[[33]]: “Beam’s Transaction Graph Obfuscation” [online]. Available: https://github.com/BeamMW/beam/wiki/Transaction-graph-obfuscation. Date accessed: 2018‑12‑24.

[33]: https://github.com/BeamMW/beam/wiki/Transaction-graph-obfuscation “Beam’s Transaction Graph Obfuscation”

Appendices

This section contains some information on topics discussed in the report, details of which are not directly relevant to the Grin vs. BEAM discussion.

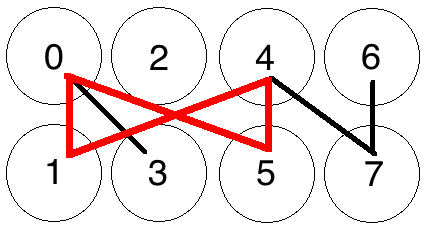

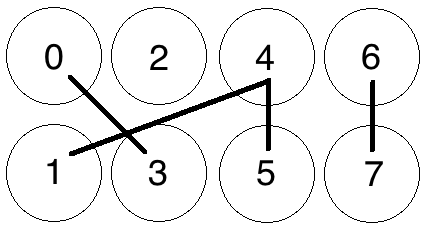

Appendix A: Cuckoo/Cuckatoo Cycle Proof-of-Work Algorithm

The Cuckoo Cycle algorithm is based on finding cycles of a certain length of edges in a bipartite graph of N nodes and M edges. The graph is bipartite because it consists of two separate groups of nodes with edges that connect nodes from one set to the other. As an example, let’s consider nodes with even indices to be in one group and nodes with odd indices to be in another group. Figure 2 shows eight nodes with four randomly placed edges, N = 8 and M = 4. So if we are looking for cycles of length 4, we can easily confirm that none exist in Figure 2. By adjusting the number of edges present in the graph vs. the number of nodes, we can control the probability that a cycle of a certain length exists in the graph. When looking for cycles of length 4, the difficulty, as illustrated in Figure 2, is that a 4/8 (M/N) graph would mean that the four edges would need to be randomly chosen in an exact cycle for one to exist [29].

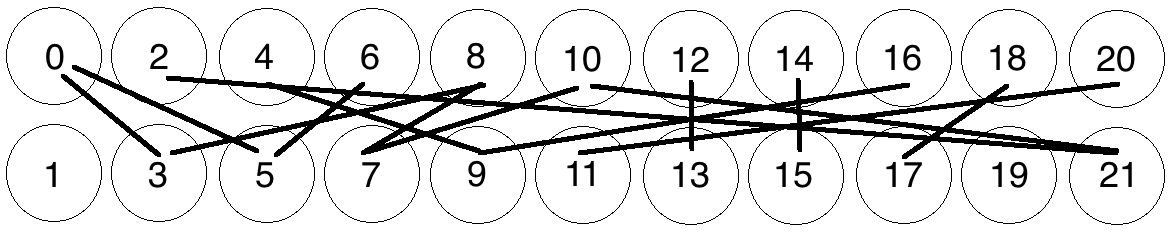

If we increase the number of edges in the graph relative to the number of nodes, we adjust the probability of a cycle occurring in the randomly chosen set of edges. Figure 3 shows an example of M = 7 and N = 8, and it can be seen that a four-edged cycle appeared. Thus, we can control the probability of a cycle of a certain length occurring by adjusting the ratio of M/N [29].